Blog

Strengthening State Endangered Species Acts to Conserve Biodiversity

October 28, 2024

With 34% of our nation’s plant species and 40% of our animal species at risk of extinction, state action can halt and reverse biodiversity loss.

State Endangered Species Acts (SESAs) are one tool that can aid in recovering biological diversity. SESAs complement the federal Endangered Species Act by providing additional resources for recovering federally listed species while also keeping state-listed species off the federal list. They also often reflect regional considerations and allow states to set ecosystem-wide priorities. As of 2024, Puerto Rico and 47 states have endangered species laws.

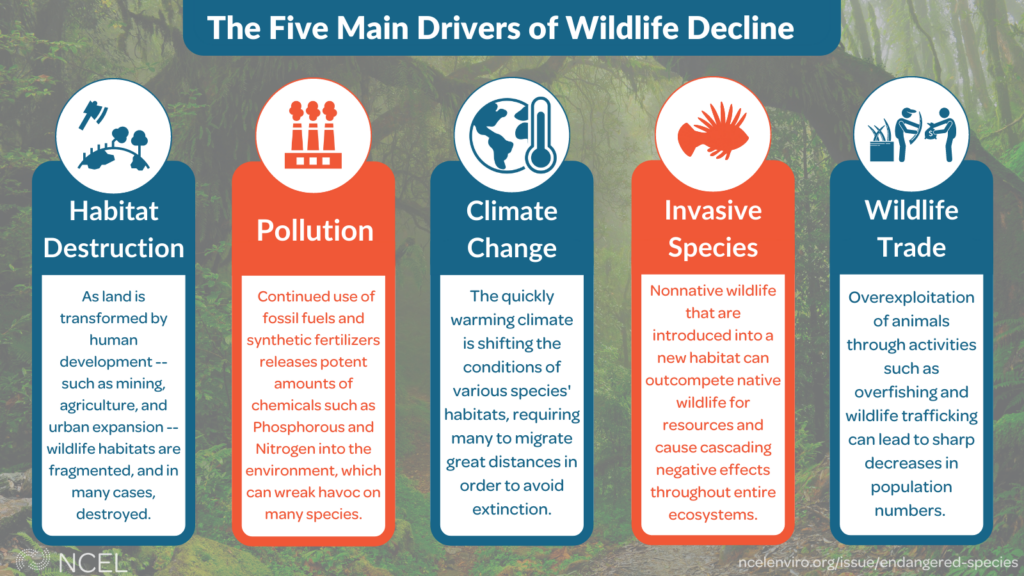

A majority of states enacted their SESAs shortly after the federal ESA’s passage in 1973. Today, climate change, invasive species, habitat loss, species exploitation, and increased pollution present challenges for states’ endangered species conservation and management.

In 2022, NCEL took a deep dive into each state’s SESA to assess if state laws were keeping pace with changing realities.

The report showcases that many state laws can be improved to meet today’s challenges and outlines policy options for how states can improve their laws. NCEL recently conducted follow-up interviews with wildlife agency staffers from states where NCEL identified gaps in their endangered species policy based on our 2022 report.

Below are four of the key highlights from the 2024 report update:

Update 1: Clarification of How States Define Wildlife

NCEL’s new report provides enhanced clarity for what wildlife species are covered under state statutes. Each state with a SESA defines what animal and plant species may be protected and conserved under their state’s endangered species statute. The prior report reflected that all 47 states with a SESA protect “wildlife” in one form or another. Our updates now provide a more instructive definition by covering what’s included or excluded in that definition.

Examples

- Invertebrates are either excluded or have uncertain protection under 20 (18 states and 2 territories) SESAs, while Idaho excludes predatory species from its SESA protections.

- Endangered plants are not covered within all states’ endangered species legislation.

- Only 18 states plus Puerto Rico protect all plant and animal species.

Update 2: A Summary of 2023 and 2024 Enacted Endangered Species Legislation

Seven states (CA, CO, ME, MD, PA, SC, WA) enacted 12 SESA-strengthening bills in 2023 and 2024. These bills sought to modernize the state laws to be more responsive to challenges facing each state.

- Maryland enacted HB 345/SB 916 which widens the state’s definition of wildlife, allowing for invertebrates to be protected. The law mandates that recovery plans be updated at least every five years to ensure conservation actions are in line with the best available science. Read more at NCEL’s policy spotlight.

- Maine HP 794 amended the Natural Resources Protection Act to include endangered and threatened species’ habitats under the state’s protective “significant wildlife habitat” categorization.

- Colorado enacted HB 24-1117 which gives the state’s Department of Natural Resources the authority to protect, study, and conserve invertebrates and rare plants. Such authority is intended to give the Department resources for conserving these species and allow for easy cooperation with private landowners as there are no penalties for the take of invertebrates or rare plants.

- South Carolina H 4047 prevents the general release of location-specific information for endangered species. Prior law compelled the Department of Natural Resources to disclose endangered species’ locations for any request, which left state-listed species such as bog turtles and venus fly traps vulnerable to poaching. Location requests can still be made for educational, scientific, or conservation purposes.

Update 3: Transformative Fiscal Actions by Massachusetts, Colorado, Utah, and Washington

Washington, Colorado, and Utah have bolstered their states’ funding for biodiversity and endangered species conservation in the absence of much-needed federal funding, anticipated by the federal Recovering America’s Wildlife Act (RAWA). These states instead created “mini-RAWAs” that allow for much-needed and overdue conservation to occur. These states anticipate the funding will significantly increase their staff positions, monitoring efforts, and habitat restoration projects.

- Colorado HB 23-1274 creates a dedicated endangered species trust fund with an initial appropriation of $5 million in 2023. This year, the state passed SB 24-230 which imposes a new production fee on oil and gas development to fund offsite mitigation, with 20% of the estimated $20-50 million annual revenues going to the state’s Parks and Wildlife Department.

- Washington SB 5950 appropriates $23 million for biodiversity conservation with a portion of funds earmarked for threatened and endangered species protection. Plans for additional yearly appropriations are also underway.

- Utah HB 518 appropriates $2 million to the Endangered Species Mitigation Fund bringing the total value of the Fund to $5.5 million for at-risk species conservation. This is the single largest appropriation to the Fund to date. Over 60 new projects received funding from the increase.

Meanwhile, Massachusetts’ FY 2025 Budget created a biodiversity trust fund to aid the Department of Fish and Wildlife’s biodiversity and natural systems conservation efforts. Funds are to be spent on purchasing lands, managing habitats, restoring ecosystems, and more.

Update 4: Mainstreaming Biodiversity in Decision-Making and Enforcement.

Most interviewees stressed that there is a need to move beyond solely protecting state endangered species and instead to focus on overall biodiversity protection measures such as mainstreaming biodiversity in decision-making and enforcement efforts.

- States looked to a 2023 (No. 618) Massachusetts Executive Order directing the Department of Fish and Game to conduct a review of existing biodiversity conservation efforts and establish goals and strategies to achieve a “nature-positive future” as a useful coordinating policy.

- One interviewee expressed a desire for more enforcement measures for SESA violations, stating: “The penalties for violations were so weak, that there is little impetus for protection or listing”. Meanwhile, another interviewee indicated that the need for more law enforcement is “absolutely critical” as only a small percentage of violations are prosecuted.

The United States is at an inflection point with the ongoing loss of the nation’s biodiversity. Fortunately, there are numerous success stories of states saving previously imperiled species. Updates to SESAs can strengthen existing state laws and ensure that our nation’s natural heritage is enjoyed by generations to come.